|

PRESS RELEASE | February 6, 2017

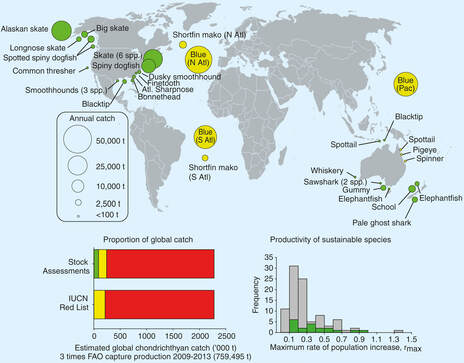

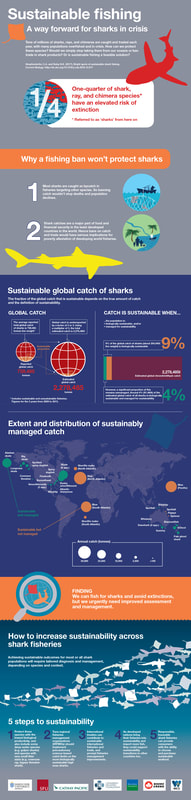

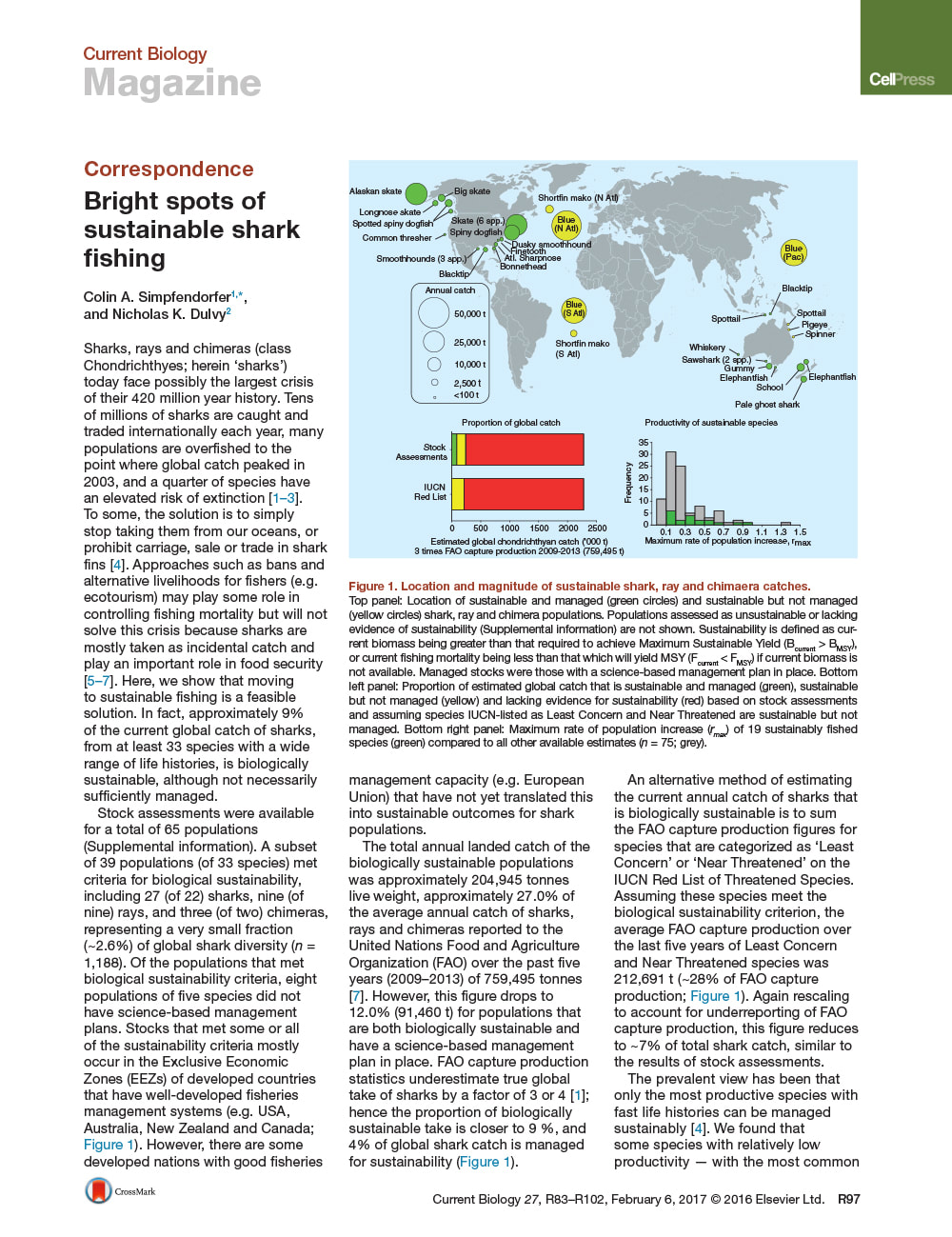

"There are two main reasons why bans on shark fishing don't work," says Colin Simpfendorfer (@SharkColin) from James Cook University in Australia. "First, most are caught incidentally in fisheries for other species, and many die during capture and handling. Second, many communities depend heavily on sharks and rays as a source of animal protein, so banning fishing may eliminate their only affordable source." There's no doubt that sharks (including rays and chimeras) are in trouble, facing possibly the largest crisis of their 420 million year history. As the researchers note, "tens of millions of sharks are caught and traded internationally each year, many populations are overfished to the point where global catch peaked in 2003, and a quarter of species have an elevated risk of extinction." In the new study, Simpfendorfer and colleague Nicholas Dulvy (@NickDulvy) from Canada's Simon Fraser University assessed data available for 65 worldwide populations of sharks and their relatives including rays and chimeras. They found that 39 of those populations representing 33 species met the criteria for biological sustainability. The sustainably fished sharks accounted for about 9 percent of the current global catch. That's more than 200,000 tons in live weight. So, sustainable shark fishing is not only possible, it's already happening in some places. The researchers offer five recommendations to help in achieving sustainable shark fisheries, which exist today in nations including the US, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand, in other parts of the world. They are as follows:

"At present the notion of sustainable shark fins is unthinkable to many," the researchers write. "Yet, today's sustainable (but not necessarily managed) shark fisheries yield ~4,406 tons of dried fins." Of course, consumers have no way of knowing today whether products they buy were fished sustainably or not. Simpfendorfer says there are many techniques to help reduce incidental catches of sharks and rays, and new innovative techniques should continue to be developed. For example, he says, the banning of wire leaders on longlines can reduce the catch of sharks. The use of turtle excluder devices (TEDs) in shrimp trawls also helps to avoid capture of larger sharks and rays. There won't be simple answers, however. That's because there are 1,200 shark species, and the challenges will be different in each country where they are found. "We need to redouble species-level data collection and increase status assessment of the most heavily fished populations so that we know how and when sustainability is achieved," Simpfendorfer says. "We can fish for sharks and avoid extinctions without banning fishing, but we urgently need improved assessment and management." They say the next step for them is to identify the lessons learned in sustainable shark fisheries and begin translating those into management recommendations that can be implemented in countries around the world. This work was funded by the MacArthur Foundation, the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation, the Cathay Pacific, Natural Science and Engineering Research Council (Canada) and the Canada Research Chairs Program. Current Biology, Simpfendorfer and Dulvy: "Bright spots of sustainable shark fishing" http://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(16)31464-6 Current Biology (@CurrentBiology), published by Cell Press, is a bimonthly journal that features papers across all areas of biology. Current Biology strives to foster communication across fields of biology, both by publishing important findings of general interest and through highly accessible front matter for non-specialists. Visit: http://www.cell.com/current-biology. To receive Cell Press media alerts, contact [email protected]. PRESS RELEASE: https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2017-02/cp-csb013117.php Reference

Comments are closed.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed