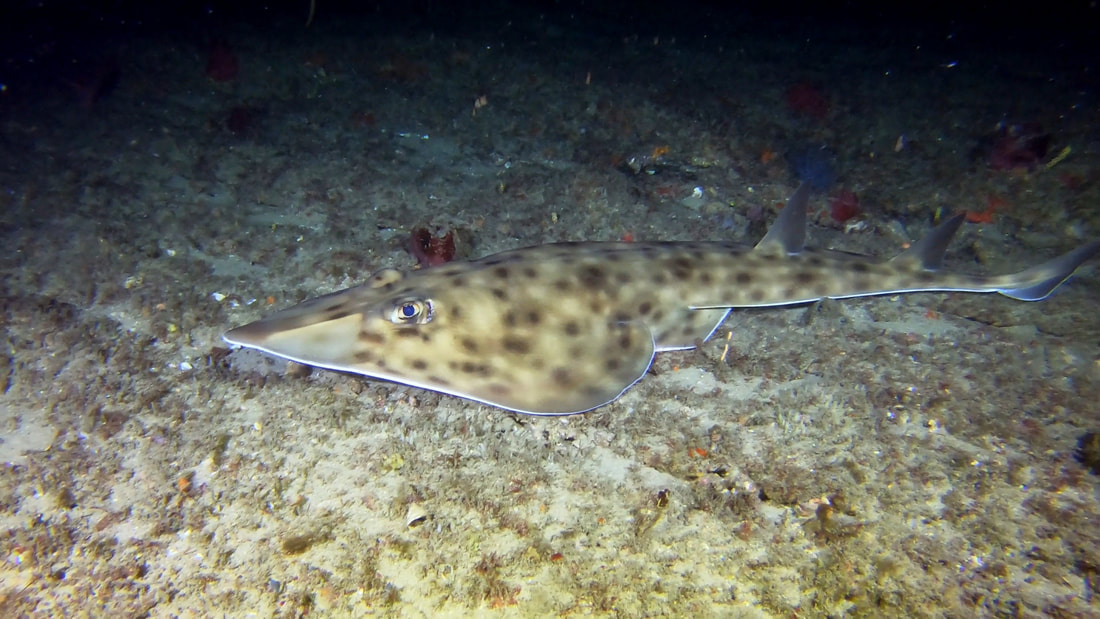

First SA Shark checklist – PublishedMakhanda, South Africa – David Ebert, (Research Associate to SAIAB) who is popularly known as the Lost Shark Guy spearheading global efforts to find and discover little and unknown sharks, has published a first of its kind monograph for South Africa’s chondrichthyan fauna. The monograph titled, “An annotated checklist of the chondrichthyans of South Africa” provides a current list of all sharks, rays and ghost sharks that occur in South African waters. Ebert said, “The monograph provides a quick one-stop reference to determine what species are found in South Africa, their distribution and their current IUCN Red List status. The monograph provides not only the current scientific names, but also the historical names, so you can trace the shark’s genealogical name.” The publication of the monograph means that conservationists now have a quick reference to determine if a scientific name is still correct or whether it may have changed. In describing each species, the monograph provides some interesting remarks about it. Among the many interesting facts about South African sharks listed in the monograph, in describing the Whale Shark for example, the monograph states: “Did you know Andrew Smith named the Whale Shark the world’s largest fish in 1828 from a specimen caught in Table Bay? Yes, the world’s largest fish was named from a specimen caught in South African waters.” Did you know that the Longnose Pygmy Shark (Heterosymnoides marleyi), an entirely new genus and shark species, was found on a beach near Vetch’s Pier, Durban in 1923? It is one of the rarest sharks in the world with only six known specimens to date. Following public concern about shark populations along the South African coast, the South African Department of Environment Forestry and Fisheries (DEFF) recently released the official report on the National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Sharks (NPOA-Sharks) in South Africa. Information on the population status and impact of fisheries on sharks is sparse. This is mainly because sharks are mostly caught as bycatch and the management and conservation of sharks is hindered by a lack of data. As a result, for any conservation plan to be effective, it requires accurate knowledge of the species involved. Therefore, for fishery and management agencies to develop improved conservation and management policies to achieve the actions of the NPOA-Sharks, a monograph like this is critically important as it shows what species exist within South African waters. Speaking on what the publication of the monograph means for South Africa and the country’s understanding of sharks, Ebert said, “Many of the lesser-known species, those that I refer to as Lost Sharks, may be disappearing before our eyes without anyone paying any real attention. For example, two sawfish species were historically known to occur in South African waters, but none have been seen since 1999, making us wonder what other species are disappearing or have gone extinct without us even knowing they existed.” This means that there is still much more to be discovered about these ‘Lost Sharks’ that may be disappearing globally and how their absence is causing serious repercussions on the environment. How about the Velvet Dogfish (Zameus squamulosus), first recorded from South Africa based on four partially digested specimens found in the stomach of a Sperm Whale harpooned off Durban in 1971. The publication of the monograph also highlights the importance of taxonomy in shark conservation, as the classifying and naming of species is integral to wildlife conservation and in providing the bedrock for our understanding of sharks. In order to develop proper conservation or management policies, it is vital to know what species exist and how they are related and thus, scientists can understand their role within the ecosystem. As one of the leading shark taxonomy specialists in the world, Ebert said that when he started working with the IUCN Shark Specialist Group 20 years ago, “there were Red Listed species that did not even exist. The scientific names had been synonymised and the species were no longer valid.” Ebert added that, “known species that should have been assessed were not being assessed.” Therefore, combined with the most recent IUCN Red List assessment, this monograph provides the most up-to-date list of all known shark species in South Africa’s waters, which will form a foundation to develop future research and improved conservation and management policies. This is particularly important as South Africa has a high number of endemic species, “it is crucial for shark conservationists to know the names of the species they are trying to develop conservation plans for,” said Ebert. South Africa is one of the top five global hotspots for chondrichthyans, only sitting behind Australia, Indonesia, Japan and Brazil. South African waters harbor 191 chondrichthyan species and one-third of the global fauna. Of these, 70 are endemic to southern Africa, meaning they are unique to the waters of southern Africa. There is also a high degree of endemism (16 species) in South Africa and near-endemism of the species represented in this monograph. Some of the unique shark species, most of which only occur in South Africa’s waters and which are listed in the monograph are the Shy Sharks (Haploblepharus) and other endemics include the Flapnose Houndshark (Scylliogaleus quecketii) and the Ornate Sleeper Ray (Electrolux addisoni). These two species only occur along a couple of hundred kilometers of our coastline and nowhere else in the world. The monograph lists that, “45% (50 of 111 species) of all shark species and 33% (24 of 72 species) of all ray species in South African waters are at risk of extinction.” These numbers vividly highlight why it is important to know what species occur within South Africa. Ebert said, “Knowing the species that occur here will help (in the short term) to give names to the individual species, so that we know what species are involved. The long-term benefit is that this monograph has laid the foundation for future research, management and conservation of South Africa’s shark fauna.” South Africa has a long rich history of Shark research going back to the early 1800s. One of the most amazing discoveries was the Taillight Shark (Euprotomicroides zantedeschia), discovered in 1963 off Cape Town, its name comes from a bioluminescent fluid it secretes from glands located at the base of its pelvic fins; this is a true glow-in-the-dark shark. There is still more to look forward to, as South Africa’s next newly named shark species will be published in the next issue of the journal Marine Biodiversity, adding one more species to the South African fauna. Are there still more new species to be discovered in South African waters? Ebert believes there definitely are. Support for this project was provided by SAIAB, the South African Shark and Ray Protection Project implemented by WILDOCEANS (a programme of the WILDTRUST) and funded by the Shark Conservation Fund, which supported Ebert in the compiling and writing this monograph. “It was a privilege for the WILDOCEANS’ Shark & Ray Protection Project to contribute to this product and to support the amazing work of David Ebert,” said Dr Jean Harris of the WILDTRUST. “This is the first published paper linked to the project – which is hugely exciting for us and South Africa. Considering that sharks and rays are one of the most endangered taxa on the planet and South Africa has the opportunity to be a sanctuary for the species, this valuable product could not have come at better time.” AcknowledgementsA monograph of this magnitude was the result of decades of research and help from numerous people, and Ebert thanks all those who have shared their knowledge and information. He said, “There are several people and organizations who were especially helpful to me in getting this monograph through to fruition. At the top of the list is my good friend Paul Cowley, who I started out with on this journey to study South Africa’s shark fauna 35 years ago. Roger Bills and the collections staff at SAIAB, especially Mzwandile Dwani, Nkosinathi Mazungula and Vuyani Hanisi who were instrumental in helping me access specimens in the SAIAB Collections Facility. A big thank you to Angus Paterson and Alan Whitfield for their research support over the past 10 years. Elaine Heemstra for patiently answering my numerous pesky questions on specimens she and her husband, Phil, had collected. My good friends and colleagues, including Robin Leslie and Sheldon Dudley (DEFF), Bruce Mann and Sean Fennessy (ORI), Geremy Cliff (Sharks Board), and Rhett Bennett and Dave van Beuningen (Wildlife Conservation Society, South Africa). Finally, I want to give a big thanks to my co-authors, Sabine Wintner and Peter Kyne, for their huge efforts and knowledge in compiling this monograph.” The monograph can be found from these links: To take action and learn more, follow: @LostSharks (Facebook), @LostSharksGuy (Twitter) and @LostSharkGuy (Instagram) The @SHARKATTACKCAMPAIGN (Facebook & Instagram), @SharkAttackSA (Twitter) and sharkattackcampaign.co.za/take-action/.

Comments are closed.

|

Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|